![Sue[4]](https://alumline.source.colostate.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/11/2019/03/Sue4.jpg)

By Whei Wong Howerton

“He called me Squaw.”

That’s the first time Susan Devan Harness (M.A., ’06, ’16) remembers realizing she was different. Her classmate used the derogatory term describing an American Indian woman or wife. She was in third grade.

At 18 months, Susan had been removed from her Flathead Indian Reservation and adopted by a white Montana couple. During that time in the ’50s and ’60s, the Indian Adoption Project removed almost 400 American Indian children from their mostly western reservations and placed the majority of them into homes in the east. The Project received more than 5,000 applications from prospective parents.

“My mom just wanted a baby. She had suffered half a dozen miscarriages,” says Harness. “She wanted to be a mother and I was the first available. My dad, on the other hand, just wanted to save a poor, neglected Indian baby.”

It’s estimated, by 1974 thirty percent of all American Indian children had been forcibly removed and placed in non-Native homes. Later, Harness would discover she was one of three middle siblings of nine children removed by social services and placed away from her tribe – the Confederated Salish and Kootenai tribes.

“I always knew I was adopted, always knew I was American Indian,” Harness says. “When I asked about my birth parents, I referred to them as my ‘real’ family. I was told they had died in a car accident. Dad said, what do you mean your real family? We raised you, we clothed you, we fed you. Don’t ever talk about your real family. We are your real family. That’s when I was 7.”

Harness grew up an only child in a rural Western Montana town. Racism against American Indians in Montana is second only to that in Alaska.

“There are 7 Indian reservations in Montana. Everyone has a story about a run-in or experience. The stories were very negative,” recalls Harness. “You’d get beaten up for being proud of Indian heritage.”

When she started researching her biological family in her early 20s, a move her adopted mother supported, she discovered her birth mother was actually still alive. She was living 30 miles away on the Flathead Indian Reservation. That search for identity and Harness’s challenging reentry into her Native community would change her path.

“When I met my birth mom, she looked more like a photo in an Edward S. Curtis book than me. She had very strong American Indian features.

“That meeting was not easy – not the romanticized version we like to think about. She spent a good portion of our first meeting staring down at her lap crying. There was a lot of shame because she had lost three of her nine children to social workers.”

Studying transracial adoption issues and outcomes has become her life’s work. Harness received both her master’s in cultural anthropology and a master’s in creative non-fiction from Colorado State University, where she also served as a research associate with the Tri-Ethnic Center for Prevention Research at CSU. She recently shared her work along with her own story during CSU’s celebration of International Women’s Day. The theme: resilience.

“What happened to me as part of that social experiment? It decimated a native culture. What happened to an entire generation of us?”

Harness only met with her birth mother four times before she died. Today, she’s close to three of her biological siblings. She continues to share her story and connect with transracial adoptees across the country.

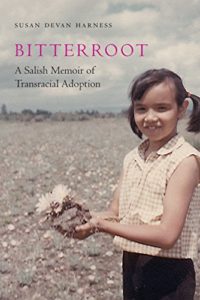

In her recent book Bitterroot: A Salish Memoir of Transracial Adoption, released October 1, 2018, Harness examines her life in the context of the uneasy intersection of race, history and the government American Indian policies that affect the lives Native families.

In her recent book Bitterroot: A Salish Memoir of Transracial Adoption, released October 1, 2018, Harness examines her life in the context of the uneasy intersection of race, history and the government American Indian policies that affect the lives Native families.