Fancy Cheptonui (M.S., ’23) has always been focused on understanding why things happen. Especially as it relates to climate change. Growing up at the edge of the Mau Forest Complex in the Rift Valley region of Kenya, Cheptonui would be filled with a mixture of wonder and concern whenever the forest would erupt into flames during the summer season.

“I knew something was fascinating about why the forest would catch fire, and I wanted to understand why it’s happening, what impact it has on the atmosphere, and what is the long-term impact on the environment,” she said.

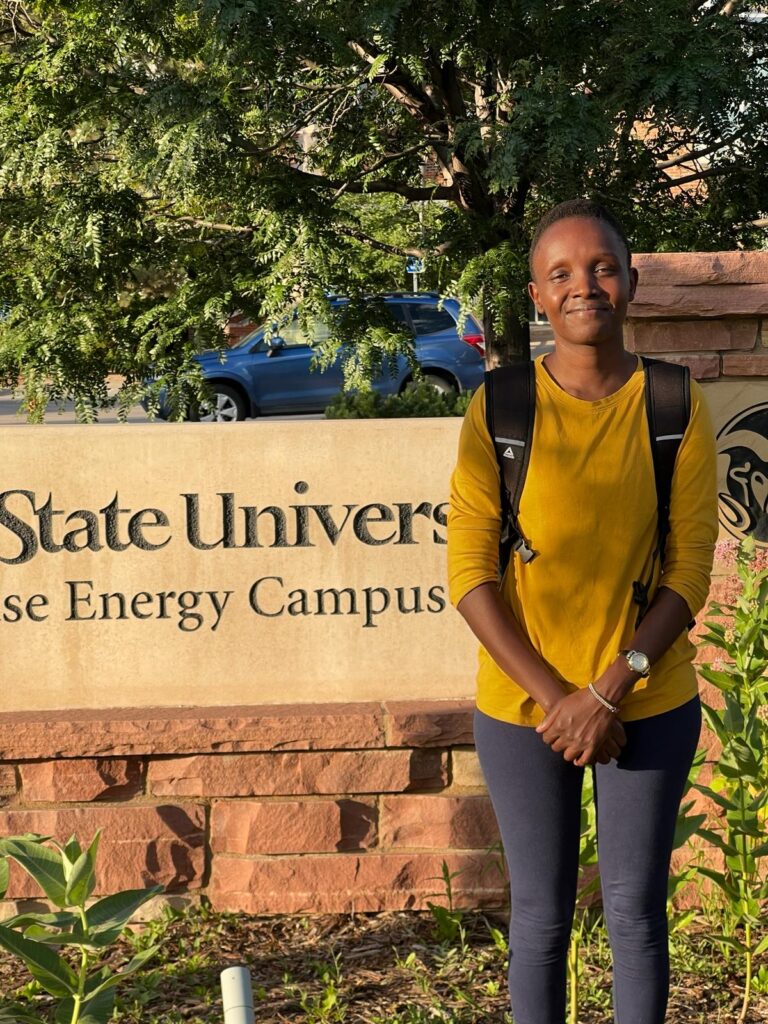

After earning her undergraduate degree in petroleum engineering from Kenyatta University, which allowed her to combine her interest in climate change with her love of math, chemistry, and physics, Cheptonui wanted to take her education further. That’s when her mentor suggested Colorado State University.

“I started filling out my application in March 2020 and was accepted for the Fall 2020 semester, but that was the period when we had COVID. I started remotely and was doing my classes from my moms’ kitchen,” she said with a laugh.

Once things opened back up, Cheptonui was able to come to Colorado and work toward her master’s in systems engineering in-person. Unlike Kenya, Cheptonui said, Colorado has a robust oil and gas industry that provided the perfect proofing ground for her lab- and field work, even if it took some adjusting to the climate.

“My advisor had done a good job of warning me how bad the winter would get, but I don’t think I took it too seriously,” she said. “I found myself in the field one day alone with the snow [up to my eyes] and had to call for help. My friend came to get me and said, ‘we are not [out in the field] on these kinds of days.”

Cheptonui survived the winters, and now, armed with her master’s, she’s working toward a Ph.D. in systems engineering at the Methane Emissions Technology Evaluation Center at CSU’s Energy Institute.

“The experience at the Energy Institute has been amazing,” she said. “The people there are so helpful, and if you make a mistake you not only get corrected, but someone always follows up to ensure you’re doing things correctly and learning.”

The goal of her research, which is as complex and complicated as both the oil and gas industry and climate change, is to track and reduce fugitive emissions at oil and gas facilities. Unlike venting or flaring, which are planned emissions that help reduce pressure and serve as a safety check, fugitive emissions are unplanned releases of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, Cheptonui explained. Regardless of if the discharges are accidental or the result of faulty equipment, they can be especially harmful to the environment – natural gas is approximately between 85 to 90% methane, which is one of the most potent greenhouse gases and contributors to climate change.

“Methane can stay in the atmosphere for 12 years and traps heat more than any other greenhouse gas,” Cheptonui said. “And fugitive emissions account for a large part of [methane] that accumulates in the atmosphere.”

That’s where Cheptonui’s research comes in, which is specifically focused on improving the remote, continuous monitoring systems used by oil and gas companies to detect fugitive emissions.

“My work right now is focused on testing these leak detection and quantification systems to help companies see how their systems are performing before they deploy it in an actual oil and gas facility” she said.

The importance of the remote, continuous monitoring systems, she added, is that emissions data is collected in real time, 24-hours a day, and can be reviewed and monitored from anywhere. That can help identify patterns, zero in on a leaky equipment, and be able to prevent a major accident before it happens.

“Fugitive emissions can happen any time of day, and with these systems in place you’re able to go into the field and mitigate it immediately,” Cheptonui explained. “Without these systems in place, you could come back the next morning and find that everything has blown up.”

When it comes to oil and natural gas, there’s also the risk of explosion, but as it is for many researchers, most days are not quite that exciting. Mostly, Cheptonui’s days are filled with setting up instruments, running tests, gathering data, analyzing it, and doing it over and over again to help develop a model that can be applied out of the lab and in the real world. It may seem monotonous, but the end result will be developing a system that can accurately measure fugitive emissions and keep the energy in the oil and gas equipment instead of in the atmosphere.

“We can’t ignore the fact that we need energy, but at the same time we cannot ignore the impact of energy production on climate change,” Cheptonui said. “Making production better, mitigating the problems associated with production and transportation, and establishing long-term methods that reduce fugitive emissions is the best way forward.”

Not just for the oil and gas companies, but for the climate, the planet, and all of its inhabitants. That’s what keeps Cheptonui in the lab at the CSU Energy Institute, because helping reduce the impact of climate change isn’t just about satisfying the curiosity she’s felt about the world since she was young.

“I have a daughter back in Kenya, so every morning I wake up thinking one day she is going to see what I’ve been doing and be proud of what I’ve done,” Cheptonui concluded.