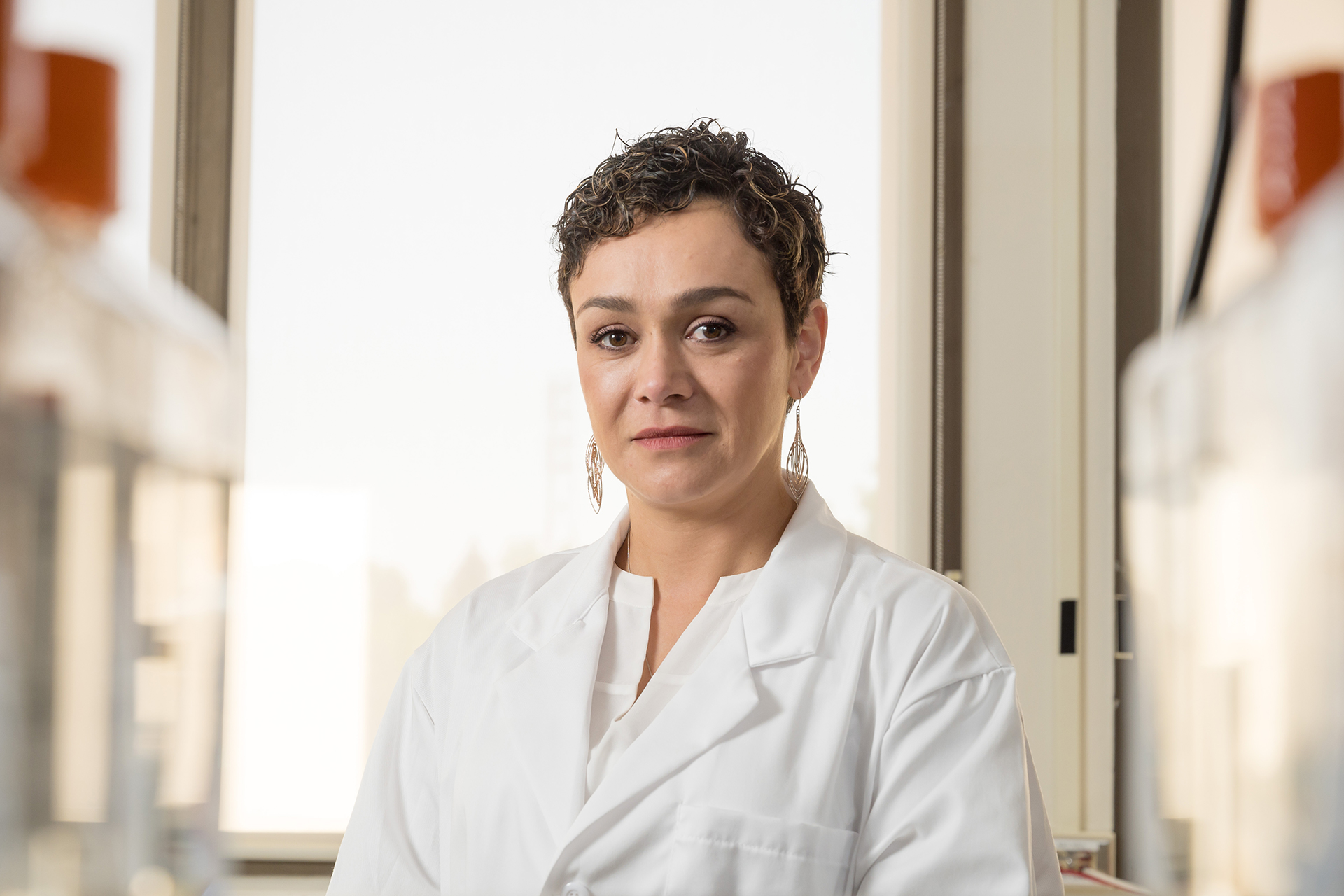

Assistant Professor Marcela Henao-Tamayo in the Immune Mechanisms of Protection Against Tuberculosis Center. Photo by John Eisele/CSU Photography

For International Women’s Day, SOURCE sat down with Marcela Henao-Tamayo — an assistant professor in the Department of Microbiology, Immunology and Pathology and director of the Flow Cytometry Core at Colorado State University — to discuss her tuberculosis research, COVID-19 vaccine projects and Women’s History Month.

Q: Tell us a little bit about your background.

Marcela Henao-Tamayo: I initially went to medical school in my home country of Colombia to become a family practitioner. When I finished, I started doing clinical research with tuberculosis (TB) patients in Colombia which has a much higher rate of TB than in the U.S. I ended up doing my master’s in clinical sciences in Colombia and was spending my time working on TB and with patients. I was sampling blood to see if people had any genetic disposition to the disease. My TB research brought me to CSU, where I initially came to work for a year as a research scientist. I learned I didn’t have all the basic sciences knowledge I wanted, so I got my Ph.D. at CSU. My research since has been focused on understanding how the body responds to tuberculosis in terms of immune response. I believe it is better to prevent the disease rather than to just focus on treating it. I’ve been working on many TB vaccine candidates. However, once COVID started, I’ve begun work on many of those in helping them evaluate the immune response. I was also a dancer as a young woman, and becoming a professional dancer was my dream as a young girl. I went into medicine but learned that appreciating the arts makes you a better scientist and person.

Q: Why is tuberculosis research important today?

MHT: Tuberculosis has been with humans for a long time; we’ve even seen it in mummies. It’s a complex pathogen that has learned to live in our bodies and evolve with us. For some reason, the human body has not learned how to prevent TB yet even though it’s been with us for so long. It’s a debilitating disease impacting many people in many developing countries. COVID has taught us that it’s important for humans to try to prevent diseases, but TB is a pandemic that has been living with us for centuries.

Q: Tell us about the research you’re doing on COVID-19 vaccine projects at CSU.

MHT: I’m collaborating with many different teams. Before the pandemic, I had only really worked on TB, but I have a strong background in immunology and studying immune responses. I started with the SolaVAX vaccine, one of the first teams that was working on an inactivated COVID vaccine. I am collaborating with Dr. (Richard) Bowen evaluating other vaccine candidates and the immune response they induce. I was also included in a team doing a BioBank at CSU, and I was able to collaborate with Dr. Elizabeth Ryan evaluating clinical human immune responses. Much of the work on SARS-CoV-2 requires Biosafety Level 3 labs, where I’ve had a lot of experience working on TB research. I’ve collaborated with Dr. Mary Jackson, a researcher who is redirecting BCG — the best-known shield against TB — into a possible COVID vaccine candidate. There’s also the pan-coronavirus research led by Dr. Gregg Dean, where we’re looking at how the viruses might change and evolve over time and investigate a pan-coronavirus vaccine.

Photo by Trout Buesser/CSU Social

Q: What inspired you to begin research in the field of infectious disease?

MHT: One of the things I saw living in Colombia was the difficulty developed or developing countries have keeping up with infections like TB or COVID. I think we should know more about these infections because working to prevent it can save a lot more people than combating it. This is my way of helping the masses and preventing the negative impact of infectious diseases.

“One of the things I saw living in Colombia was the difficulty developed or developing countries have keeping up with infections like TB or COVID. I think we should know more about these infections because working to prevent it can save a lot more people than combating it.”

— Marcela Henao-Tamayo

Q: What does it mean to you to be a woman in STEM?

MHT: It means we have to try to be the best that we can, but we also have to support other women, especially those who want to have a career in the STEM field. It’s a very difficult career for everyone, but one of the most important things I learned is the need to support others. Show others they’re capable of being a woman in STEM, guide them, and take them seriously.

Q: What advice do you have for future female scientists?

MHT: If that’s their passion, they should pursue it. Try to enjoy the road; you might cry many times, but the journey is also beautiful. Enjoy the road you’re on and the time in the lab. Don’t believe in stereotypes. When I finished medical school, and was headed to clinical sciences, someone asked me, “How are you going to have the time to have kids and get married?” I had two kids, one when I was finishing my Ph.D. and the other during my postdoctoral fellowship. Don’t let anyone make you believe you can’t do it. There will be times where you have self-doubt, and that’s normal. During those times, look up to your support and role models to keep you going, because they’ve gone through a similar situation. Choose your friends and partner wisely, because it’s better with good and supportive company.

Q: March is Women’s History Month. Who are some women who inspire you?

MHT: The first person who inspired me was my mother. A Latina who got her master’s degree from UC Berkeley and was a professor in Colombia. She showed me that as a woman I can have a career and family, and that anything was possible. The other person who always inspired me was my grandmother who wasn’t allowed to go to high school but kept learning on her own her entire life.

Scientists who inspire me include many of the women in science in Colombia who are close to me and who I’ve known since my time in medical school.

Katherine Johnson, the NASA mathematician, was a woman of color in science who inspired me and so many others to do more than we ever thought possible.